I spent a lot of my days in the car. I drove around our beautiful country – sometimes from one end to the other – offering various business services to people. I remember these “cruises” for a few specific things. Firstly, I often went to my interlocutor’s to “watch the clock”. Even though I had telephoned the cues for the meeting, the meeting (read: the interlocutor) showed a different face and ended without any potential for cooperation. A complete waste of time and money …

Secondly, in the days without the aid of a navigation system, finding a house in some exotic village I had never heard of before was quite an interesting experience… Well, when mobile phones came along, it was made a lot easier.

And thirdly, these drives have stayed in my memory after a constant battle with the clock and speed limit signs.

It usually looked like this. I’m driving down the road, looking at my watch and thinking about the meeting. Because I am lost in my thoughts, I also miss many speed limit signs. Of the ones I do notice, many seem pointless: “I understand that these limits are suitable for inferior vehicles or inexperienced drivers… But for me, they are completely pointless.” Sometimes I get into a bit of a game, wondering which restriction is more pointless than the last.

Of course, all this had an impact on my driving. I found myself either driving at the limit – which seemed very slow or a waste of time – or deliberately speeding.

Speed limits as a symbol of operational limitation

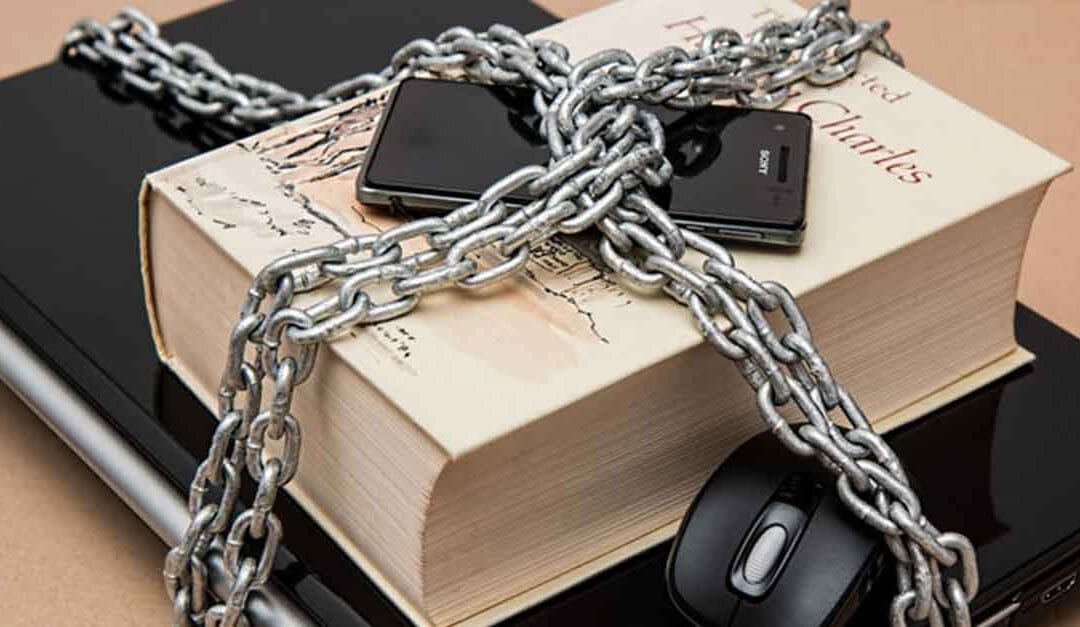

This kind of view is a pretty good symbolism of most things that happen in life. We often feel trapped in circumstances that make us feel uncomfortable. We struggle with rules, dogmas, attitudes, traditional principles, etc., which we don’t like or don’t give us the feeling that we are gaining anything from them, but rather that they are limiting us – we cannot express ourselves fully and we are not free.

What is even more interesting is that it is often only when we are fully aware of the rules that they start to cramp us. It is as if we are looking for something to resist. For example, we lend a book to a friend that we haven’t picked up for years. A few days later, we want to read that very book …

If we are not aware of what we are doing, this kind of edge-walking creativity can become a habit and perhaps even our primary mode of expression. But we can also change this pattern.

The simple solution

The solution is simple: if we have no possibility to change the rules, let us accept them as an unshakeable fact, as something definitive.

If we can grasp the situation in this way, we are liberated.

The rules constrain us as long as we allow ourselves the possibility of breaking them. We resist what we think can be tamed or overcome. This is manifested by our minds drifting into a comparison with other possibilities.

When we accept certain circumstances as irrefutable, our perspective changes. The new circumstances become the playground on which we express ourselves. Just as in a game of sport, we accept the rules and express our potential within them.

Let’s look at this solution through some practical examples.

Liberation through choice

So we have two choices: either fight or challenge the rules (more or less), or accept them completely.

Let’s return for a moment to the example of driving at the speed limit. Until we take full responsibility for our driving or have a very clear view of speed limit signs, we are confused and inconsistent. We act chaotically or on a feeling or impulse. We may be driving by the rules, but it feels strange … because we have in mind that there is also the possibility of going faster. We may drive within the limits in certain areas – usually in zones where there might be cops – but break them in other areas. Or we drive above the limits, and when our conscience kicks in (read: we think about our wallet), we slow down.

We can also choose the worst option: driving slightly above the limits all the time and feeling uncomfortable with either the rhythm of the driving or the violation.

Regardless of our driving style, our attitude to traffic rules takes a lot of energy.We look out for a speed camera … or perhaps a police car hiding behind a tree or building … or a driver in an oncoming car who has just given us a friendly “honk” to warn us of a blue light, etc.

When we accept restrictions as a “necessary evil”, which we will comply with 100% of the time, the story changes completely. In this case, we decide in advance that our driving will be based on speed limits no matter what.

Of course, we shouldn’t expect things to just fall together, or to switch from one driving mode to another in the blink of an eye.

The transition to a new mode of perception requires firmness and steadfastness

It will take some miles to stop resisting the inner voice that will force us to transgress. The challenges will be great: we will feel that we are driving extremely slowly and that this is “not us” (not our rhythm). We may even be honked at by lorry drivers who will “stick” to the back of the car. We will have the feeling that we are working in a column. We will be counting down the minutes as we drive, wondering whether we will arrive at our destination on time. Our minds will be going ‘I just need to push a bit here, otherwise I’ll drive by the rules’ and so on.

How much we actually give in to this voice depends on our inspiration and our final decision. And in fact, that is the key to everything.

The right decision is the one that closes the door to other options or leaves no room for doubt. If we “decide” to do a certain thing, while leaving ourselves some safety nets, we are not really making a decision – we are merely leaning to one side and then allowing circumstances to shape the way things go.

This is not the best way to go, because we have not really changed anything. We will still operate in the old, established way and we will still succumb to temptation in times of crisis. In that case, the results will be the same as we are already getting. We have only created a false sense of moving forward. (The biggest bounces happen in two situations: in everyday life, when we can change our routine and consequently break free from the shackles of inertia, and in times of crisis or greater pressure, when we make a different choice than we would normally have made.)

Once we have made a decision so consistently that everything else that remains outside this possibility is practically non-existent for us, a lot of problems disappear.

If we manage to persevere long enough for the new way of doing things – based on 100% compliance with the rules – to become our new comfort zone, we have finally achieved liberation. We no longer feel bad because we are no longer bothered about what we are losing. If we remind ourselves of the benefits of our new choice, we may even feel very good…

A key view of the situation

The example of driving within limits is merely a symbolism for accepting circumstances that we cannot change. Sooner or later in life we will come to a situation in which we feel trapped. (Note: many people see this way of looking at a situation as an expression of creativity. However, a distinction needs to be made between creativity in the sense of considering the circumstances and expressing oneself through them, or creativity in the sense of wanting to be creative through changing the circumstances.)

This is very clearly illustrated in the treatment examples. Sometimes circumstances will require us to be unwaveringly consistent: in the timing of treatment … in the precise execution of procedures … in the use of specific devices, preparations and raw materials, and so on.

Above all, this type of situation will require our full commitment and trust in the process and in the successful solution. If we trust, we will persevere. If we do not trust 100%, we may follow the procedures in principle, but our minds will wander to finding shortcuts and alternative solutions, exploring new possibilities and so on.

In addition, faith, which manifests itself through an unwavering decision, also gives us a placebo effect. It can even tip the balance in the outcome of a treatment. It does not only have the effect that sometimes a sugar pill (without any curative effect) produces a healing change, but also that a treatment process that would have worked less well without this “add-on” works better.

The difference between a bad and a good cook

Let’s look at another example. Two chefs in two different restaurants are faced with an impossible task. They are running low on ingredients, the dining room is crowded beyond description, their assistants and waiters are panicking … and they have just learned that a very distinguished group of diners is coming and expects nothing less than perfection from the restaurant. (This is communicated to them personally by the restaurant owners, who tell the chefs to do their best and do it as best they know how.)

The first chef would like to put down his apron and take a holiday, because he has realised that this is too much for him. He is convinced inside that he cannot do the job well, but he will do it anyway – feeling that he is underpaid for his work … that no one notices his efforts … that no one takes notice of him and understands him … that no one helps him when he needs help the most … that he is the one who gives the restaurant its stamp of approval, but no one acknowledges him … and that someone else will profit at his expense again. He is panic-stricken because he does not have the right ingredients for any of the recipes. (Hint: this is a very realistic illustration of how we create a sense of suffering within ourselves.)

The second chef is by nature more “curt”. He says to himself, “I’ve been through worse” and instantly accepts the game. He opens the fridge and looks at the ingredients he has available. He quickly assesses the options, decides on a basic recipe – which he will adapt as needed – and doesn’t even think about the other potential options (read: “How nice it would be if …”). New ideas are bouncing around in his head on how to use the existing ingredients to create a masterpiece.

What limited the first chef, challenges the second, or encourages creativity. New circumstances have arisen which now define the framework for action. There is no point in fighting against them, wondering “Why is this happening to me?” and so on, but to accept the rules of the game as soon as possible and start – to play.

When discipline and consistency lead us to suffering or bad feelings

The key difference is therefore in comparing the status quo with an apparently better situation or potential. The more energy we put into comparison, the worse we will feel and the less energy we will have left to create. At the same time, we will be less focused on action and our intuition will shut down.

One step further is to see the situation as a sacrifice of short-term gains at the expense of long-term well-being. In this case, there will be a sense of giving something up; most often at the expense of some other goal. “I don’t feel great, but it’s worth it – when I reach my goal, all will be forgotten and the effort will be rewarded many times over”, we may say to ourselves. We may also wonder whether it is worth it, or where the line is between consistency and discipline and working against oneself.

The very concerns that we have are enough to tell us that we have not set out on the right path. Our foundations are too weak because the decision was not final.

(Incidentally, there is another downside to this way of working. By the feelings we express, we create an energetic state within ourselves at every moment. This is then reflected both in our body and in our choices: in the way we look at ourselves, at others and at the world.)

Unwavering resolve makes suffering impossible

The 100% or final decision creates specific circumstances in which suffering cannot exist; not even in theory.

Suffering always comes from comparison. We think about the situation we find ourselves in, and at the same time about the other options that are available, or could be available. We ask ourselves what we are losing by choosing a new path and what we would have had if we had stayed on the old path.

When we catch such feelings in ourselves, we need to go back to the basics. If we deal with the problem at this level, we will probably never finally solve it.

Our first and only task should be to consolidate the decision.

Practical help with decision-making

The easiest way is to write and compare the reasons in favour of the decision with those against. Take a piece of paper and divide it lengthwise into two halves, left and right. On one side, write down all the reasons that support the decision, and on the other side, those that do not. (On the other hand, let’s not use this process as an excuse to procrastinate; in the sense of, “I’ll take the time to cover all the possible and theoretical situations… which could take weeks”.)

Next to each reason , write a score from 1 to 10 to indicate its importance or strength. For example, “I will no longer have so much time to watch TV” is rated 1, and “Definitive solution to a long-term, persistent problem” is rated 10.

Then add the scores of the left and right columns. Almost certainly, the sum of the positive effects will be much greater than the sum of the negative ones. Save the sheet and keep it in a visible place. This way we will pick it up repeatedly, thus reinforcing the flow of thoughts and feelings that lead us in the right direction.

Another advantage of this procedure is the logical approach, which is based on long-term benefits. Often we make decisions based on emotion and short-term gratification. When we take the time to actually evaluate all the pros and cons on the one hand and the benefits and drawbacks on the other, we no longer perceive the situation in a one-dimensional or impulsive way. (By the way, bad feelings and suffering almost always stem from the search for instant gratification.)

This article is based on the book “The Big Ugly Crisis”, by Boris Vene and Nikola Grubiša.